2 Effecting Global Change

Heavenly Father’s children are blessed by sustainable built environments. But changing our society and cultures to emphasize sustainability is not easy, particularly not on a global level. In this chapter, we will study how elements of teamwork and leadership can help amplify our ability to effect change in the world around us.

2.1 Self-awareness

- Identify your Myers-Briggs personality type and Johari Window profile using provided tools or surveys.

- Describe how self-awareness contributes to effective communication and collaboration within diverse teams.

Getting through life is easier when we have a good understanding of our own strengths and weaknesses. We can recognize our weaknesses and get help from others – including Christ through the Atonement – to augment our own natural abilities.

And if men come unto me I will show unto them their weakness. – Ether 12:27

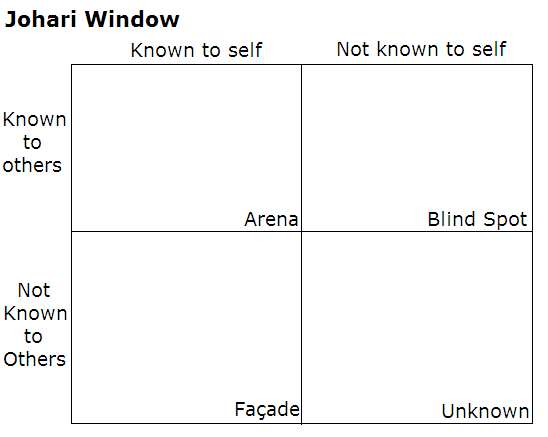

The Johari Window is a tool developed by Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham to help therapists explore issues related to self-awareness and internal conflict. Pictured in Figure 2.1, it is based on attributes of our inner selves that are known or unknown to us, or that are known and unknown by other. The arena is the parts of ourself that we know, and that others are able to see and understand. Attributes that are obvious to others but not to ourselves create blind spots, potential pitfalls in our relationships with others. Attributes of ourselves that we know but don’t want to reveal to others are in the facade, or a construct we show the world while living with some conflict about it. And then there is the unkown, elements of ourselves we have yet to discover.

In general, the more parts of ourselves that are in the arena, the more dynamic and effective our relationships with others will be.

What facade are you building, or attributes about yourself you feel you have to keep unknown from others? What can you do to move these attributes into the “arena”? What is keeping you from doing this?

The Swiss psychologist and philosopher Carl Jung developed a hypothesis that people experience the world through four psychological dimensions: 1. sensation 2. intuition 3. feeling 4. thinking

In work heavily based on Jung’s theory, Katherine Briggs and Isabel Myers developed a classification scheme originally released in the 1960’s and refined in subsequent decades. The Meyers-Briggs Type Indicator relies on dichotomies on four dimensions:

- Extroversion or Introversion – where the focus of our attention is, and where we derive energy to acommplish work.

- Sensing or iNtuition – how we take in information about the world around us.

- Thinking or Feeling – the way we make decisions about what to do.

- Judging or Perceiving – how we approach the work we do.

It is important to understand that the terms applied to these dimensions are not necessarily used in the same way we use them in common speech: A Judging person in the Meyers-Briggs dichotomy is not necessarily more judgmental, but rather they approach their tasks with judiciousness, and an Introverted person is not necessarily shy but rather derives energy from individual thought instead of engagement with others.

The combination of the four dichotomies leads to a classification scheme of 16 personality types; an introverted, intuitive, thinking, and perceiving person would be called INTP. These dimensions are also spectrums, and many people are not entirely one or the other. In fact, data from Meyers-Briggs tests themselves show that along these spectrums the distribution of the population is largely normal, and not bimodal as might be expected were these true dichotomies.

Many people believe that Meyers-Briggs types can help people choose professions that best match their personalities, but in truth almost any personality type can be successful in almost any profession. And teams with multiple personality types are stronger, provided that the differences in individual world view do not create conflict that distracts the team from its goals.

Numerous scientific approaches have challenged different aspects of the validity of the Meyers-Briggs indicators. But they do introduce a method for talking about diversity in teams. If they are useful to you, then use them. If they don’t help you see yourself better, feel free to ignore them.

2.2 Goal-oriented teamwork

- Describe the stages of team development using Tuckman’s model, and provide examples of team behaviors in each stage.

- Identify characteristics of effective teams and explain how they contribute to successful project outcomes.

- Create a mission-oriented task plan that outlines roles, goals, and deadlines for a team-based assignment.

A team is a small group of people committed to a shared purpose. The members of a team have complimentary skills, mutual and individual accountability, and work both interactively and independently. When teams are successful, they accomplish considerably more work — and work with greater impact — than the members of the team could possibly accomplish individually.

The opening lines of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina are as follows:

All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

Though all families are different, happy families are universally committed to kindness and respect, and honor their covenants with each other. Teams are much the same way; well-performing teams all share some similar characteristics. These teams:

- Have a clear and shared vision. This includes refocusing the initial vision when new problems arise.

- Establish a collaborative and inclusive environment, where all the viewpoints of team members are considered and valued.

- Clearly communicate with one another.

- Set goals, planning tasks as stepping stones to meet them.

- Divide and conquer according to strengths and weaknesses. Assign team roles based on individual strengths. Of course, developing new individual strengths and talents is often a goal of teamwork.

- Build awareness of each team member’s roles. This requires good communication, but it also helps the team develop respect for all its members.

- Celebrate successes.

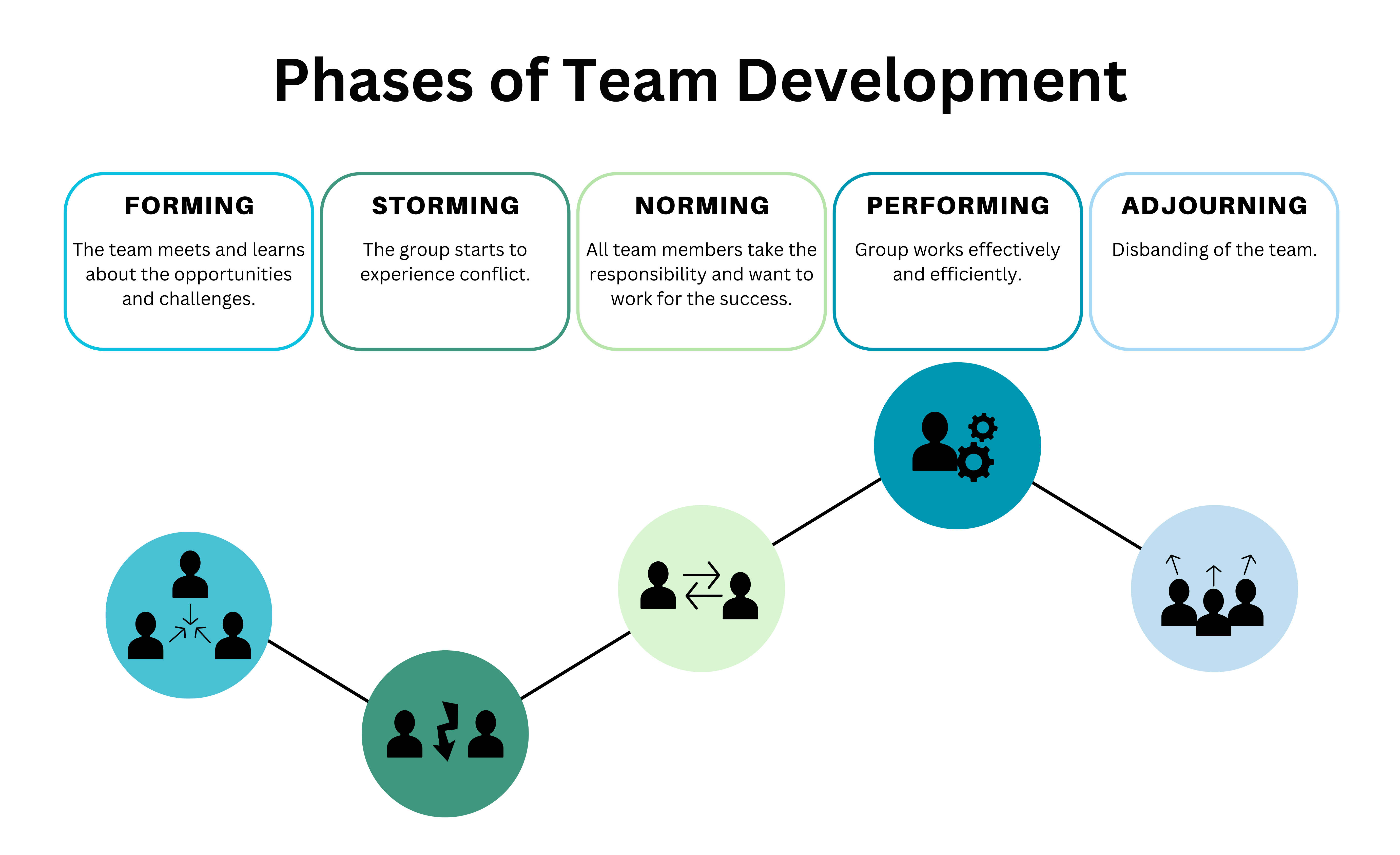

When a team is created, the team goes through stages of development. Tuckman (1965) identified 5 stages, illustrated in Figure 2.2. In the forming stage, the team is just getting to understand each other and their objectives. This can immediately lead to storming, or the rise of conflict as the team has disagreements about what their goals are. Unsuccessful teams never pass this point, but successful ones establish standards for performance and accountability, a process called norming. Finally, the team reaches its performing output before disbanding.

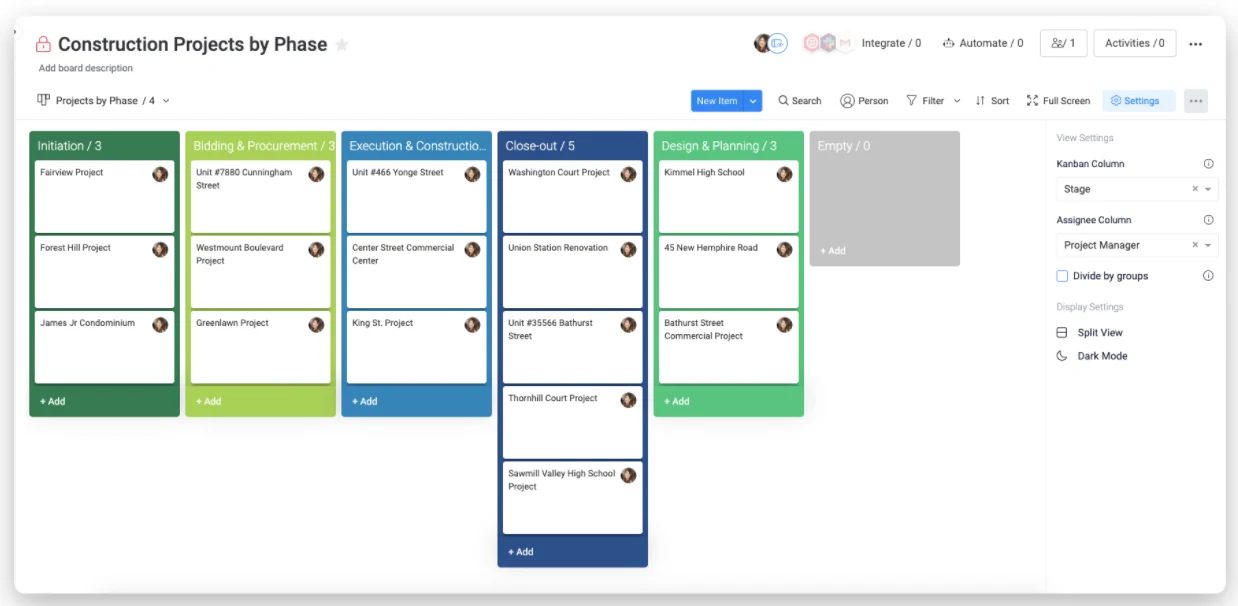

Scheduling and task-focused teamwork is crucial to successful teams. Mapping out and scheduling benchmarks helps keep everyone on the team accountable and unified. In order to achieve a large goal, smaller goals are made. These goals should be specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-based. Each team member should be aware of the deadlines. By scheduling tasks the team is oriented toward a common goal. Many teams benefit from using some kind of formal project management system. These may include:

To do lists.

Kanban boards: these boards map out multiple tasks or ideas through all stages of development, from instigation to completion. Refer to the example of a construction project board Figure 2.3.

Task and team management software like Asana or Wrike or even GitHub helps keep team members abreast of what needs to be done, make assignments, and track task completion. These software usually place to-do lists or kanban boards alongside communication or time tracking features.

The best task management strategy is the one that you will use.

2.3 Performance Indicators and Feedback

Individuals and teams would obviously like to perform at their best. But what is the best? Who decides what good performance entails? What can a team do to learn whether their performance is at the level they want? It is important thefore for teams to define Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and receive other forms of feedback.

The goal of a sports team is generally to win games, and thereby championships. Easy! But how a team approaches this overarching goal requires more fine-tuned attention. Does offense or defense win the most games? Who knows? We’ll be fighting about this for the rest of time. But successful teams generally track performance along a more specific, quantifiable set of performance indicators that lead to the goal.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (see Section 1.4) are lofty, general goals akin like “end poverty in all its forms everywhere.” This is a goal similar to “win games.” But progress toward these goals are tracked with specific indicators, such as “the proportion of people living on less than $2.15 per day.” We can continue this exercise:

- Goal: Get an A in this class.

- Indicator: Complete each pre-class assignment and submit each homework assignment on time.

- Goal: Complete the term project on schedule.

- Indicator: The number of slides in a completed state at the end of each week.

- Goal: Be a kinder person.

- Indicator: Number of days you have reflected in your journal on how you treated others.

A general strategy to developing KPI’s is:

- Establish an objective: Define the goal that the KPI will measure.

- Outline the criteria: Identify the data that will be used and ensure its integrity.

- Choose a measurement methodology: find the right way to collect the information needed.

- Define and document performance measures: Use KPIs to drive the right behaviors and activities to achieve better results.

- Assign responsibilities for KPIs. Who will track the indicator and report on it?

- Regularly evaluate progress toward goals through KPIs.

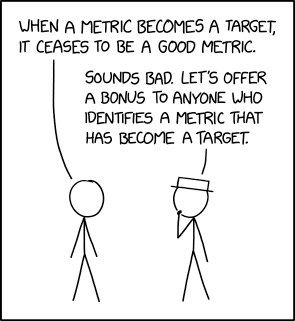

Of course, it is possible to become overly obsessed with indicators. Goodhart’s Law (see Figure 2.4) is often stated as

When a metric becomes a target, it ceases to be a good metric.

College entrance examinations like the ACT were originally designed to assess how well a student is prepared for college-level work. But with the weight assigned to your ACT score, you probably took preparation classes and practice tests designed to maximize your ACT score. So, now the ACT instead is a measurement of how well a student prepared to take the ACT.

Don’t mistake your KPI as a replacement for the actual goal! And if you are killing it on a KPI but you still haven’t reached your goal, reflect on whether you need a new KPI.

2.3.1 Sustainability performance indicators

How do you quantify and measure sustainability? Many organizations have established voluntary sustainability standards for the built-environment. LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) is one of the first and most-widely used sustainable building rating systems in the world (U.S. Green Building Council 2022). LEED was started in 1998 by the U.S. Green Building Council to develop a system to define and measure a green building (Baker 2018). LEED provides a helpful definition of green building.

Green building is a holistic concept that starts with the understanding that the built environment can have profound effects, both positive and negative, on the natural environment, as well as the people who inhabit buildings every day. Green building is an effort to amplify the positive and mitigate the negative of these effects throughout the entire life cycle of a building. In practice, it builds upon the classical building design goals of economy, utility, durability, and comfort. By enlarging the scope in this way, green building provides project teams a more robust framework to incorporate the three pillars of sustainability (people, planet and prosperity) in their projects. (U.S. Green Building Council 2022)

LEED certifies buildings according to “energy use, water use, indoor environmental quality, material selection, site and location within the surrounding community”(U.S. Green Building Council 2022). According to LEED, “LEED-certified buildings typically consume 25% less energy, reduce carbon emissions by 34%, and use 11% less water” (Verdinez 2024). As of 2024, there have been over 195,000 LEED projects. Most are in the US, but there have been projects in 186 countres (Verdinez 2024), including Brazil as shown in Figure 2.5.

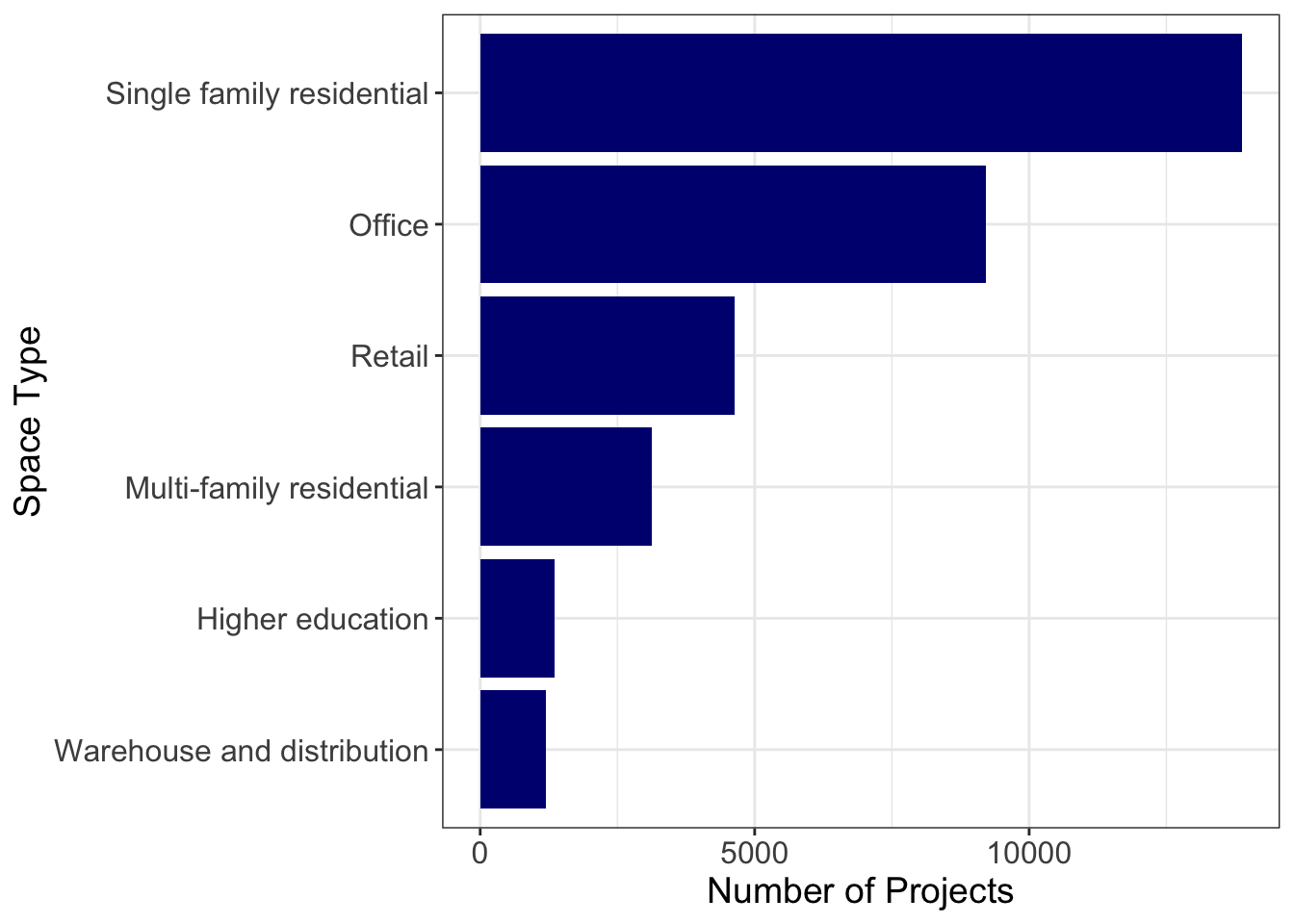

LEED certifies projects of all kinds. A distribution of the number of projects by type over the years 2017-2021 is included in Figure 2.6. There are also separate LEED scorecards for other scales, including for interior design, neighborhood development, and entire cities.

LEED has different certification requirements for buildings depending on the stage (new design and construction, existing buildings) or type of building (including single-family residential, multiple-family residential, office buildings, hospitals, warehouses, retail and schools). To achieve LEED certification, buildings require certain requirements, such as conducting a climate resilience assessment, and then require a number of credits among distinct areas with different possible options, such as reducing light pollution or managing rainwater in the sustainable sites category.

LEED v5 is the latest LEED certification version, emphasizes three impact areas:

- Decarbonization

- Quality of Life

- Ecological Conservation and Restoration

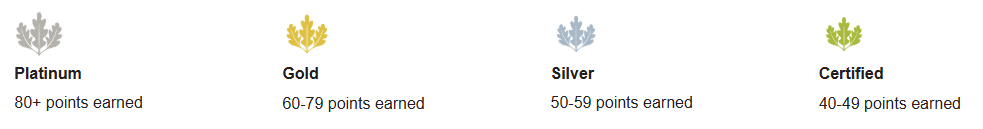

Within Quality of Life, are new requirements for climate resilience assessment, and new credits for equitable use of resources (U.S. Green Building Council 2025). Take a look at the LEED v5 scorecard for Bulding Design and Construction. Total credits earned across all categories are classified into certification levels as shown in Figure 2.7. (U.S. Green Building Council 2022).

Could you still build a sustainable building without LEED-certification? If so, do you think LEED-certification verification and branding is worth the cost?

LEED certification offers substantial benefits, such as third-party verification, transparency, corporate branding, and potentially long-term savings on energy and potenially higher long-term property values. (Carden Company 2019) LEED certification comes with a cost. One construction company reports different estimatings, one ranging from 1 to 5% of the total costs for LEED certified or Silver rating, to another reporting 10% or more. Projects in areas of less stringent building codes and inexperience of the builders and engineers, could cost increase the building cost more than 25% of the conventional building costs. Just the cost of the LEED certification process and documentation for a project are estimated between $20,000 and $60,000 as of 2019 (Carden Company 2019).

At its outset, LEED was criticized for focusing on new construction, when the most sustainable approach is generally to retrofit existing buildings whenever possible. LEED now encompasses a wider range of project types, but there is still sometimes criticism over a lack of context sensitivity (Zarghami and Ahmad 2025).

2.3.2 Feedback

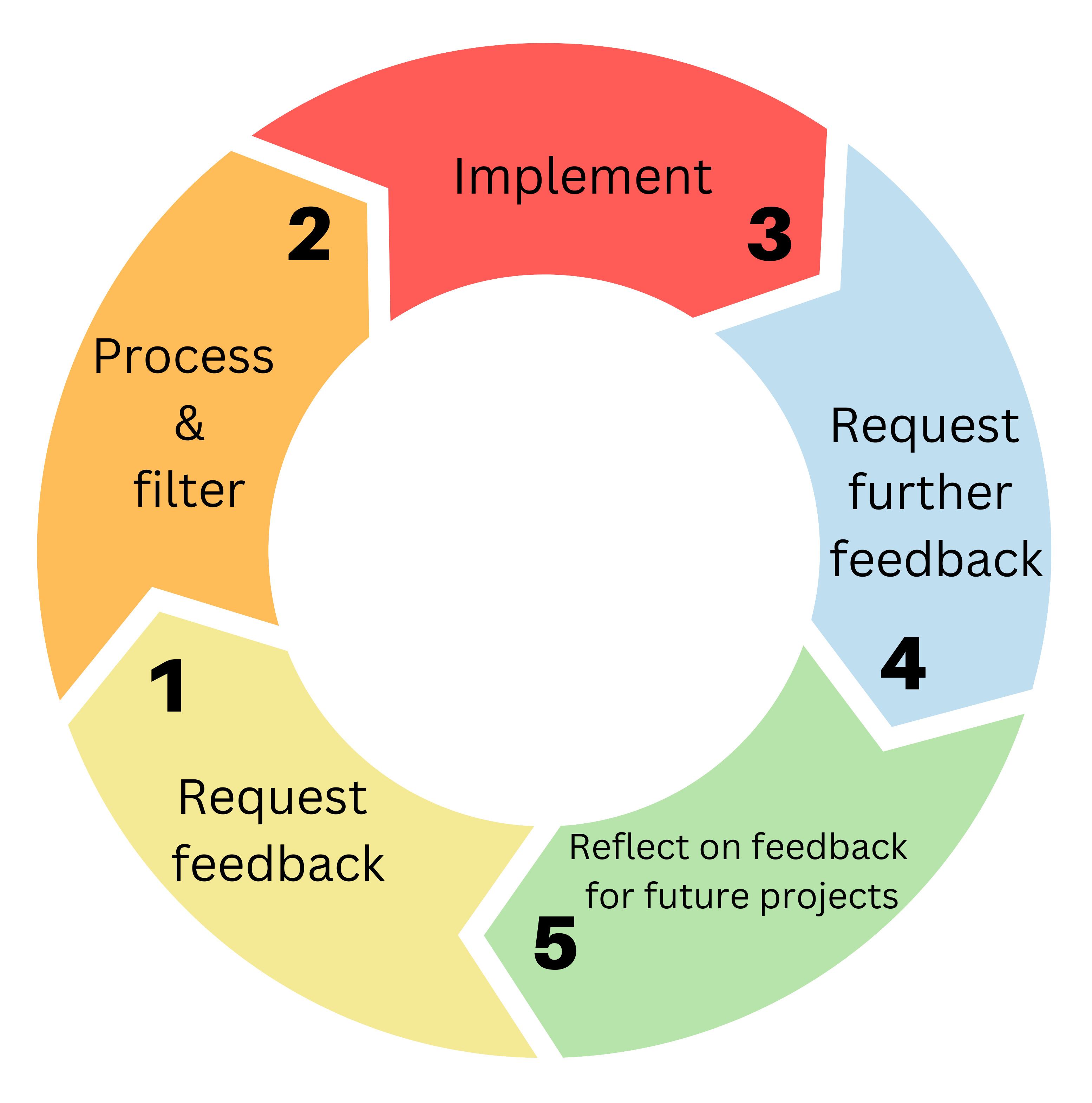

Feedback is critical when using key performance indicators and working towards a goal. By creating specific KPIs, feedback comes more naturally. We can see if we are meeting the measurable indicators and adjust accordingly. Feedback does not just happen once, but should be planned for and recieved continuously (see Figure 2.8). A successful team plans how they seek and receive feedback within and outside of their team throughout all phases of project development.

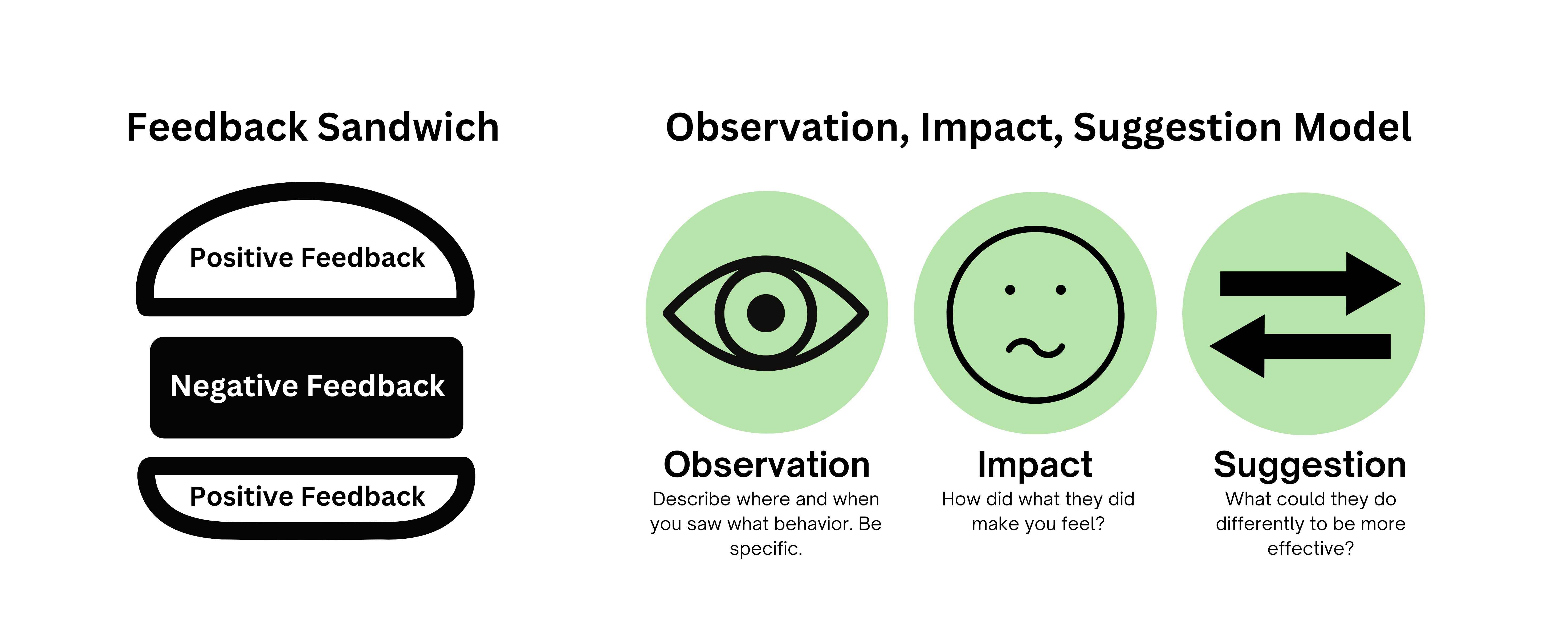

Feedback can be informal. Text messages to a colleague who missed a meeting may help your team stay accountable to each other or reveal issues in your team cohesion. Short messages of support (“good job on this slide!”) can reinforce that the work is valued. Effective feedback is both kind and clear; it should be possible to both give and receive feedback that is rooted in performance and an understanding of each person’s humanity. Figure 2.9 provides a couple of models for this. The “feedback sandwich” suggests placing substantive and constructive criticism between a “bun” of positive elements:

I enjoyed your presentation; you might think about this other thing. I look forward to seeing what you do next.

It is also important to provide feedback on elements that the person can actually act on. Giving comments on a presenter’s accent is usually pretty useless to them (and to you).

Feedback can also be formal. Regularly scheduled performance reviews help employees know where they stand, how their work is valued, and what corrections they might be able to make. KPI’s are another form of formal feedback, with a documented process for collection and assessment.

When I teach a class, I look at the students and get a feel for things based on informal cues like body language (how many people are asleep or on their computers). I also get formal feedback through student evaluations. Both help me! Sometimes they are confusingly in conflict!

You should provide student evaluations that can help your professors improve. But you should also think about the feedback you send informally.

2.4 Leadership

- Identify the role of strong leadership in sustainable built environments.

- Apply Christ’s example to personal and team leadership.

- Distinguish between multiplier and diminisher leadership behaviors.

Leadership is a constant in the built environment, even when no one hands you a title. On job sites, in design meetings, or during stakeholder negotiations, engineers are regularly called on to make decisions that affect project relationships and outcomes. Successful leaders reach beyond technical knowledge, acting as agents who claim responsibility for the broader impacts of their work. This is foundational to safety, sustainability, and social impact in the built environment. By providing clear direction and support, leaders help team members understand their roles, feel valued, and stay motivated. While quality leaders are essential in sustainable infrastructure, that leadership should extend beyond the narrow confines of your careers and into a plethora of other contexts in your personal lives. Whether you are navigating a group project for a college course, a church calling, or relationships with family or friends, leadership plays an important role in how you and others thrive.

Civil and construction engineers who mentor their teams and encourage open dialogue often prevent costly miscommunications and reduce turnover. Christlike leaders multiply the effectiveness of others by helping them develop—not just directing them.

2.4.1 Becoming a Christlike Leader

At BYU, we believe the most transformative leadership begins with discipleship. Following Christ’s example means cultivating personal righteousness while also striving for competence in our academic and professional fields. It means living true principles and exercising stewardship as we manage time, people, and resources in a way that reflects His character. In his address “Becoming a Disciple Leader,” President Kim B. Clark defines leadership as “the work that mobilizes people in a process of action, learning, and change to improve the long-term viability and vitality of organizations in three ways:

- People experience increased personal growth and meaning in their work and lives,

- Purpose is realized more effectively,

- Productivity is strengthened.

Clark outlines three core elements of Christlike leadership: leading with soul, heart, and mind.

Soul: A disciple-leader is anchored in moral clarity. Like Christ, we lead by choosing what is right, not what is easy. In the built environment, this means upholding safety standards, resisting shortcuts, and advocating for equitable outcomes.

Heart: Christ recognized divine potential in others. Leading with heart requires relational care, empathy, and trust. It shows up on the jobsite through mentoring new team members or resolving disputes with respect and humility.

Mind: Christ invited others to step into responsibility and growth. Disciple-leaders plan strategically, invite collaboration, and seek inspiration. In project work, this includes gathering diverse input, listening actively, and adapting as new challenges emerge.

These principles are not abstract ideals — they are actionable traits that elevate leadership in any context.

We can include God in our everyday decisions. Elder David A. Bednar describes the different ways personal revelation can come to us as patterns of light. Ponder which patterns of light you commonly experience and how you can seek personal revelation more diligently.

Remember, “it has never been more imperative to know how the Spirit speaks to you than right now…do whatever it takes to increase your spiritual capacity to receive personal revelation.” - President Russell M Nelson, 2020

As we strive to align our souls, hearts and minds with the leadership Christ shows us, we can shape the very environment in which people operate by bringing in organizational light rather than darkness. Organizational light is created when leaders reflect integrity, humility, and purpose rooted in eternal principles. In contrast, organizational darkness emerges when leaders allow fear, pride, selfishness, or contention to guide their actions. This can result in environments where team members feel diminished, mistrusted, or manipulated. This stalls innovation and disengages people. President Clark emphasizes that disciple-leaders bring light into the organizations they serve by striving to be instruments in the Lord’s hands.

2.4.2 Leadership in the workplace

These spiritual principles are not confined to religious spaces. In fact, many of the qualities that define Christlike leadership are increasingly mirrored in some of today’s most prevalent leadership models. For example, servant leadership emphasizes humility, empowerment and the idea that leaders exist to serve others rather than themselves. This section introduces ideas from Liz Wiseman about leaders who multiply the talents of people around them (Wiseman 2017). of leadership training across industries. Other frameworks—such as transformational, inclusive, or ethical leadership—highlight similar values: leading with vision, building others up, prioritizing long-term impact over short-term gain, and making decisions rooted in integrity. Leaders who focus on serving their teams are consistently shown to boost morale and productivity, particularly in high-stakes, high-coordination industries like those of the built environment.

Even operating within these frameworks, every leader possesses strengths and weaknesses unique to them. It’s important to understand both so you can leverage your skills and avoid blind spots as you guide people and projects.

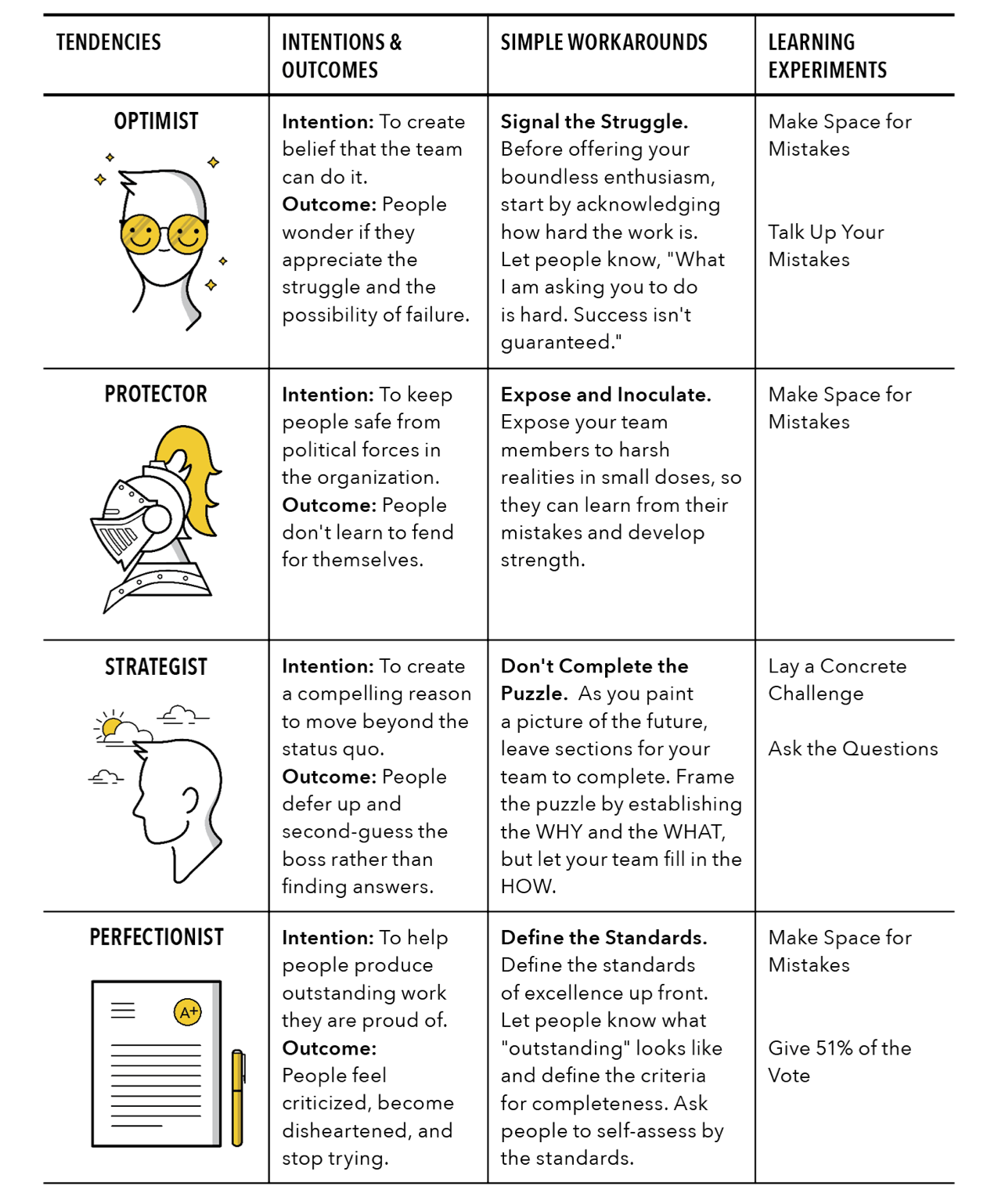

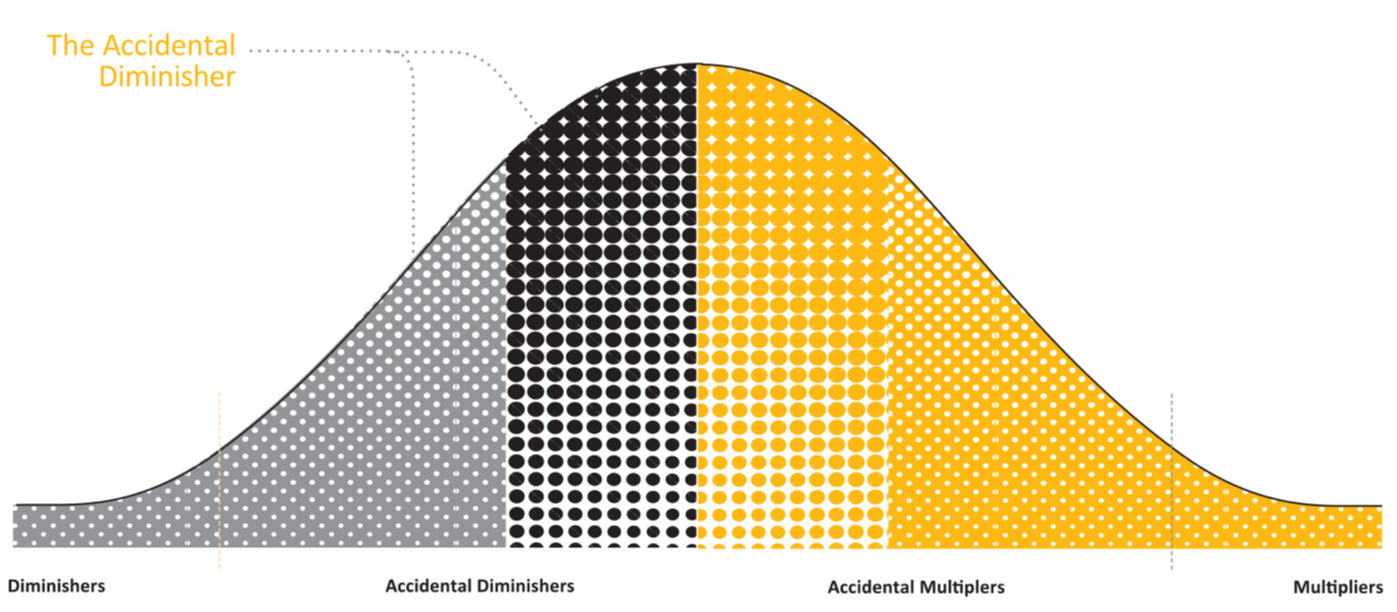

Without intending, leaders can diminish those around them while trying to do good. Most dimishing is accidental. As we become aware of these accidental diminishing traits, we can consciously become multipliers.

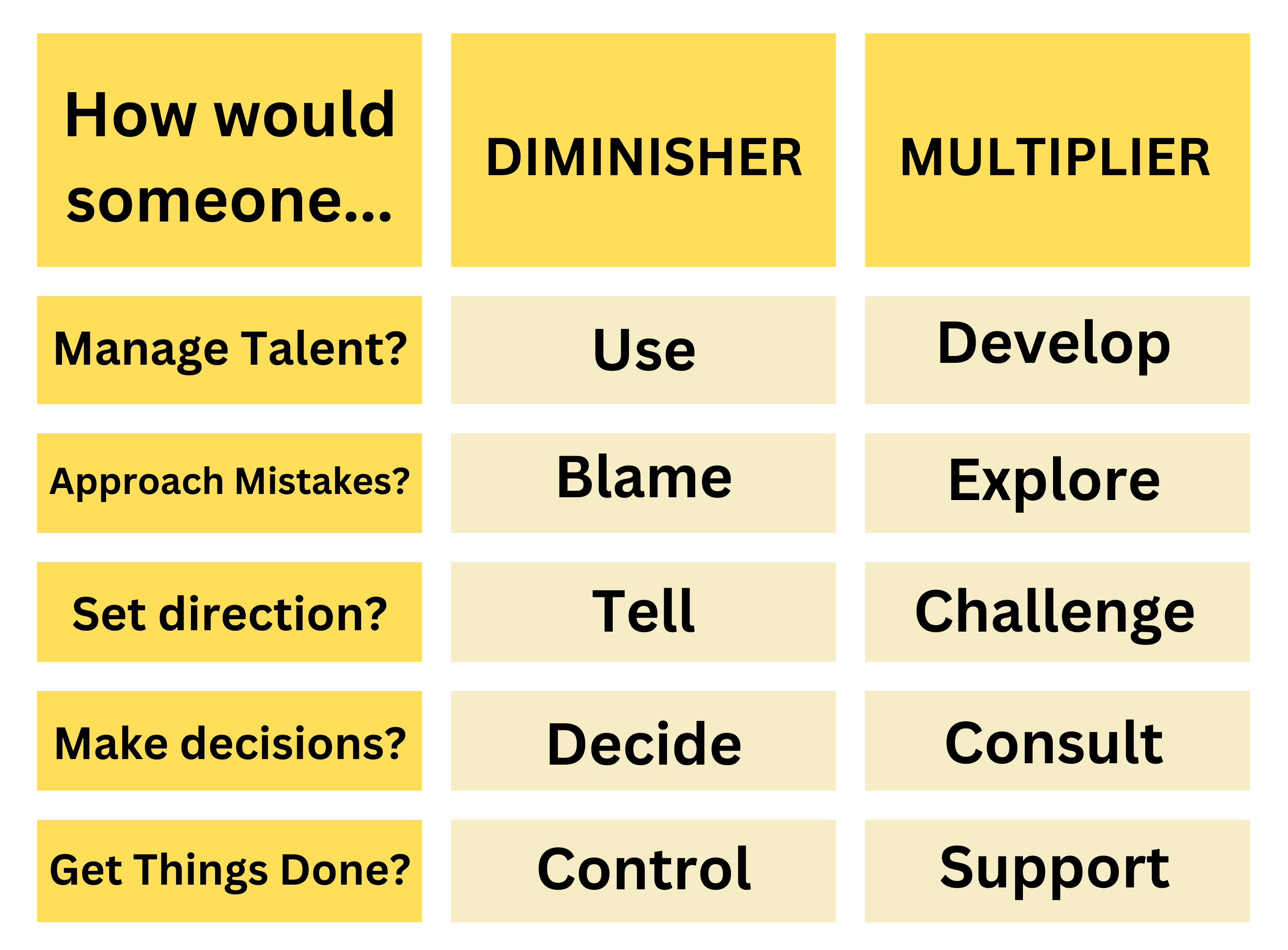

Most people are not strong diminishers or strong multiplers, but rather are somewhere in between, as shown in Figure 2.12. But with conscious effort, you can eliminate the diminisher tendencies and become a multiplier.

The Wiseman group has also created a quiz to help you identify unconscious diminisher you may have. Try this for yourself!

2.5 Impact and Engagement

- Define social impact and explain the role of civil and construction engineers in shaping positive societal outcomes.

- Explain what a stakeholder is and identify meaningful ways to engage them in infrastructure development.

- Use tools such as logic models, stakeholder maps, and/or systems maps to analyze the impact of a proposed project.

When most people think about civil and construction engineering, they imagine bridges, roads, and buildings. But they often miss the point of this infrastructure: people. From access to clean drinking water, to safe housing, to public transit that connects people to jobs and education, our work directly shapes the well-being of communities and the individuals who make them up. Because of this, engineers bear the responsibility to consider not just technical impacts, but social ones as well. History teaches us the power of infrastructure in shaping community wellness. Much of our current global infrastructure is shaped by a history of colonialism, where powerful nations built systems to extract resources from other regions without regard for local communities. Railways, ports, dams, and city plans were designed primarily to support foreign interests rather than local residents. Even after colonial rule ended, many countries inherited infrastructure systems that weren’t actually designed for their needs. Today, international development projects sometimes repeat these same patterns, albeit unintentionally. Efforts to “help” can displace local knowledge in favor of imported models, reinforcing the need for further aid from foreign groups to maintain those models. As professionals tune into the social impacts of infrastructure, sustainability can improve.

Social impact refers to the positive or negative effects a project or program has on the well-being of individuals and communities and their ability to create productive lives for themselves. A project can be structurally sound and economically viable but still fail to meet the sociocultural needs of the people it was designed for. Prioritizing social impact ensures the infrastructure we create is inclusive, responsive, and sustainable. Built environment professionals dedicated to fostering positive social impact ask questions beyond technical feasibility, such as: Who benefits from this project? Who might be left out? How will this affect people five years from now, or fifty?

2.5.1 Processes and Tools for Effective Engagement

While the process of engaging in effective social impact work may vary across professions, projects or stakeholders, a few key steps remain foundationally grounded across most approaches: Understand the problem + its context: Infrastructure is built to meet a need or solve a problem faced by people. To help, you must first try to understand the challenge they face from their own perspective. Building empathy and investing in relationships are essential to finding the true roots of problems. Familiarizing yourself with the cultural context and local nuances of the issue helps properly frame a problem to solve it sustainably. Discover how primary contributing factors to the problem directly impact your client(s). In the built environment, this can be accomplished through secondary research, advice from an expert who has successfully completed similar work, or learning from local people.

Involve the people: A solution is only as useful as its users believe it to be. By engaging people who are most proximate to the problem in every stage of your solution design process, you ensure that the solution is desired, supported, and understood by its beneficiaries. Allow them to participate in framing the problem, designing the solution, and providing feedback to offer a sense of ownership and co-creation. Survey distribution, workshops, town hall meetings, and other forms of community feedback are all viable resources for engaging local stakeholders in built environment projects.

Design + Implement Solutions: Combining your deep understanding of the problem, industry best practices, and cultural/community responsiveness, you’re now equipped to design informed, supported, and practical solutions. This involves creating actionable plans that address the needs and constraints identified by both your team and your stakeholders. Implementing these solutions requires careful planning and resource allocation to ensure that proposed interventions meet the intended goals and shape positive impact. Project management tools and regular stakeholder meetings can be particularly useful in achieving success at this stage.

Measure + evaluate: We’ll rarely get an intervention right on the first try….often, it requires repeated iterative measurement and evaluation to enact real shifts for good. People and problems are constantly evolving, and solutions will too. It’s important to collect real data regularly in order to inform the necessary pivots for sustainably improving quality of life. To know what data to capture, clearly map out the desired outcomes and impact project stakeholders wish to accomplish, and then establish a robust system to measure progress toward those end goals (complete with SMART goals and KPIs).

In addition to the basic process outlined above, problem-solvers rely on tools that aid in assessing the social impacts across the life cycle of a project.

Systems Mapping No infrastructure decision happens in a vacuum. For example, a new road project can change traffic patterns, air quality, housing prices, or school enrollment zones. A system is a group of interrelated components that form a complex whole. Systems mapping visually represents how the different parts of a system interact by depicting its components (e.g. actors, resources, or policies) and the relationships between them. It’s a useful tool for tracing connections and anticipating unintended consequences. For instance, installing a floodwall might reduce flood risk for one neighborhood while increasing runoff in another. Systems thinking invites engineers to consider these effects before finalizing designs.

Systems maps can take on various formats, but the following general procedure is applies to all layouts. Using a visual medium, like a whiteboard or a digital mapping tool:

Define your goal and scope: State the purpose of your map and determine the boundaries of your system to identify what is included and excluded from it.

Identify key system elements: List all the major components or variables within your system (organizations, resources, actions, etc). Map relationships and connections: Draw lines or arrows between elements to indicate how they influence one another, then label these connections to describe the relationship dynamic (e.g. cause-and-effect link or resource dependency).

Analyze and refine: Regularly review the systems map to identify key patterns or bottlenecks where small changes might have big impacts. Share the map with others to ensure it accurately represents the system as projects progress.

Stakeholder Mapping It takes a village to pull off a successful project, especially in the built environment. In the professional world, we call these people stakeholders. A stakeholder is any party with a vested interest in a project, organization, or decision. Stakeholders can play a role in shaping outcomes or be affected by them, and they may come from within the origin organization (such as employees) or outside it (such as customers, community members, or regulatory agencies).

Understanding who your stakeholders are is essential to project sustainability. Stakeholder maps relationally identify all the individuals, organizations, and agencies impacted by or influential in a project. Mapping stakeholders clarifies who should be engaged throughout the process. This might include residents, utility companies, local businesses, advocacy groups, city departments, funders or others. Creating a stakeholder map helps avoid blind spots and ensures diverse perspectives are included early and often throughout the span of a project.

Logic Models A logic model is like a roadmap that connects your resources and actions to intended outcomes. It helps teams focus on their goals and measure whether their work is actually contributing to them. For example, if a city builds a new community center, a logic model would track not just the construction (output), but also whether residents feel more connected to resources (outcomes). Engineers might work with planners or social workers to co-develop these metrics and review them over time. Some key definitions for logic models include:

- Input: Human, financial, and/or material resources invested in a program, such as staff, volunteers, money, supplies, equipment, and partnerships.

- Activity: The actions or work that a program performs to meet its objectives, such as providing training, teaching, mentoring, or serving meals.

- Output: The direct quantifiable results or products of the program’s activities. Examples include the number of workshops held, the number of people trained, or the number of meals served.

- Outcome: The short-term, intermediate, and long-term changes that result from the program’s activities and outputs. These can be changes in knowledge, skills, attitudes, or behaviors.

- Impact: The broad and long-term effect of the program, representing fundamental changes in the community or system at large.

Public Engagement As mentioned earlier, involving the people–or, stakeholders–in infrastructure projects is a key step in building socially sustainable futures. Community engagement in built environment projects is a structured process through which built environment professionals incorporate local input into decision-making to enhance project outcomes. Engaging stakeholders early in the project lifecycle allows engineers to identify social, environmental, and economic priorities that may not be visible through technical analysis alone. Effective engagement can reduce permitting delays, improve equitable designs, and build long-term public trust. Envision Utah, a local organization dedicated to engaging community voices in discussions about Utah’s growth, identifies the following as best practices for facilitating public engagement activities:

- Gather data to understand who lives in the community and who would like to.

- Listen to people’s ideas, visions, values and cares via methods like surveys, interviews, discussion boards, and public meetings.

- Present options and seek feedback. Options should include long-term vision, trade-offs, and a baseline version that projects current trends.

- Draft a stakeholder-supported vision and publicly supportable, actionable strategies.

Consider this scenario: On a trip to rural Nepal, you notice that most of the village’s school-aged children are not attending school. This makes sense to you, as the nearest school building is several miles away. Your team decides that building a classroom closer to the village is the perfect solution to improving educational opportunities for this group of people. You build a school within walking distance of every child in the village, and visit again a few months later to see how they’re enjoying it. Upon your return, you find the classroom empty and the children just as they were the last time you visited: out of school.

What may be some potential root causes of the problem that you failed to consider in your initial solution design? How could this have been avoided?

2.6 Ethics in Professional Leadership

- Define and differentiate between morals, norms, and ethics in the context of engineering decision-making.

- Identify common ethical dilemmas in engineering practice and describe appropriate responses using appropriate ethical frameworks.

- Interpret key elements of a professional engineering code of ethics.

Engineers and construction professionals occupy positions of trust in society. The general public expects built environments that are designed and constructed appropriately; they have to be confident that retaining walls will not collapse, or that water will not be poisoned, or any number of places where public safety depends on the built environment. Beyond this, the choices of what gets built, when it gets built, and who will benefit from it can benefit some and potentially harm others. On top of all of this, many projects are built with public funds. It is therefore essential that built environment professionals behave ethically in all circumstances.

The American Society of Civil Engineers and the Construction Management Association of America each have professional codes of ethics that their members are expected to follow. Members of the profession that violate these codes can face professional sanction, and in some cases criminal prosecution. While every professional society’s ethics codes are different, common elements of professional ethics codes include elements such as:

- Prioritize the public’s safety

- Protect the environment and the disadvantaged

- Act as a faithful agent for your clients, placing their interests above your own when in conflict.

- Treat employees and others in the profession with respect, avoiding discrimination and working to enhance diversity.

- Avoid dishonest and deceptive business practices.

2.6.1 Norms, Morals, and Ethics

It is common for people to confuse being ethical with “being a good person.” Rather than being a list of do’s and don’ts, ethics provides a framework that allows us to interrogate the decisions we make outside of cultural expectations or value judgments. It is important to understand the difference between three distinct concepts:

- Social Norms are expected practices that people in a society follow. People don’t interrupt in class.

- Morals are value judgments associated with particular behaviors. It is rude to interrupt in class.

- Ethics are guides that help you place your actions within a framework. Interrupting class prevents others’ learning.

More examples of these three concepts are shown in Table 2.1. Norms can change from culture to culture, or with time. Morals are likewise often based in religious or cultural systems that can differ or come into conflict. Ethics hopes to help people make good decisions regardless of their time, place, or background. Ethics also helps people with different moral systems agree on common best practices and decisions. Additionally, there can be norms or ethics that exist without a particular moral attachment, like beards in the BYU dress and grooming standards.

| Situation | Social Norm | Moral | Ethic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency aid | People typically help others | It is good to help someone who needs it | People in need deserve your help |

| BYU dress and grooming standards | Men at BYU are clean-shaven | Beards are evil? | BYU students pledge to follow the dress and grooming standards |

| Professional integrity | Contractors are honest | Telling lies is wrong | Your clients trust you to provide correct information |

Often these three concepts lead to the same choices. But there may be times when they are in conflict.

In the Book of Mormon when Nephi feels impressed to kill Laban and take the gold plates, is his decision based in social norms, morals, or ethics?

2.6.2 Common Ethical Dilemmas

Parents, church leaders, and school teachers have likely trained you to choose the right, and many of you are good at it. But dilemmas frequently appear in professional practice that may not have an obvious solution because norms or morals — or even ethics — appear to be in conflict. These ethical dilemmas can be challenging to resolve or navigate.

Members of the Church believe we are blessed with the Holy Ghost as a companion to help make good choices in difficult situations. But Doctrine and Covenants Section 9 teaches that having the Holy Ghost guide you in a decision requires intense study and thought. Ethical dilemmas are not alway trivial to resolve.

Many professional organizations have resources for resolving ethical dilemmas including ethics hotlines, trainings, and even legal counsel. Use these while also seeking the guidance of the Holy Ghost.

Some questions to ask yourself as you are faced with an ethical dilemma may include

- What are my responsibilities in this situation?

- Who would be hurt by the choices I am making?

- Am I caring for the most important people to me? Or the most vulnerable?

- Would I be happy if the logic for my decision appeared in the newspaper?

Agle, Miller, and O’Rourke (2016) place common ethical dilemmas into categories. Some of these are explained in Table 2.2.

| Dilemma | Definition | Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| Skirting the Rules | You could keep a rule for a worse outcome or bend it to achieve some good. | Leaning on loopholes, Letting rules define your ethics |

| Dissemblance | Misrepresenting or concealing the truth could create a better outcome. | Ruining your reputation, Making assumptions |

| Loyalty | You're not sure how much you should give up to honor a relationship. | Offloading accountability—you are responsible for your own choices, Trusting blindly |

| Intervention | You see something wrong and you're not sure how to proceed. | Signaling acceptance through silence, Acting without information |

| Conflict of Interest | Multiple roles put you at cross purposes. | Failing to recognize the conflict, Running from or hiding the conflict |

| Unfair Advantage | You have the opportunity to wield an unfair upper hand. | Justifying your abuse, Blaming the other party |

| Standing up to Power | Someone in power is asking you to do something unethical. | Assuming too much, Not protecting yourself |

| Sacrificing Personal Values | Living true to your own beliefs might impose a burden on others. | Forgetting your family in your decision-making, Seeing only yourself and your values |

2.7 Building Belonging in the Built Environment

- Describe the role of belonging in leading interdisciplinary + intercultural teams working on sustainability-related projects.

- Explain how cultural differences may affect engineering/construction project outcomes and stakeholder relationships.

- Identify best practices for developing empathy.

As disciples of Jesus Christ, we covenant to build belonging in our circles of influence. As students and future professionals working on infrastructure projects, building belonging means more than just including others. It means creating environments where people feel valued and empowered to contribute. In the built environment, this starts with how we interact on teams and extends to how we design and implement projects that shape communities. When people feel they belong, collaboration deepens and project outcomes improve, ultimately aiding sustainability efforts over time.

Belonging is more than just being included. It is the embodiment of Christ-like love based on the belief that we are all children of God, with unique experiences, gifts, and talents. It means gathering as a covenant community, being committed to serving and sacrificing, and centering our lives on Jesus Christ. Through covenant belonging we are bound to God the Father and His Son Jesus Christ and to each other. A sense of belonging is important to our physical, mental, and spiritual well-being, and to achieving our shared objective of establishing Zion. - BYU Office of Belonging

Fostering belonging reaches beyond good intentions, requiring deliberate practice. Thanks to technological advancements and globalization, we live in a world of increasingly transparent borders. This shift grants us the opportunity to regularly engage with individuals and teams from backgrounds different from our own. Developing skills like cultural intelligence, empathy, and rooting out unconscious bias helps engineers and builders recognize the lived experiences of others and build infrastructure that reflects the needs and values of diverse populations.

2.7.1 Cultural Competency

Culture shapes how we communicate, make decisions, interpret behavior, and understand the world around us. It includes visible features (language, customs, or dress, for example) as well as invisible ones (like beliefs about time, space and place, authority, nature, and responsibility). These cultural values affect how individuals approach teamwork, resolve conflict, and interpret infrastructure projects. Cultural awareness is the ability to recognize and respect cultural differences. Cultural intelligence builds on this as the capacity to work and interact effectively across cultures through reflection and adaptive behavior. In built environment contexts, this means being aware that community members, clients, teammates, and/or other stakeholders may hold different *assumptions about what matters and why.

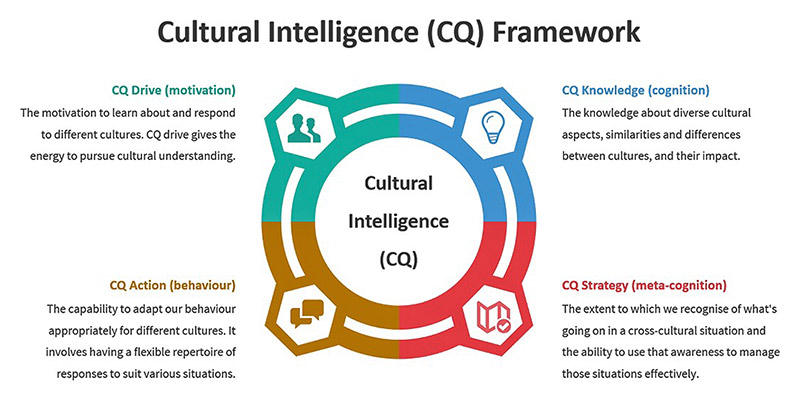

Cultural intelligence includes four core capabilities: drive, knowledge, strategy, and action. These areas help individuals assess and adapt to new cultural contexts.

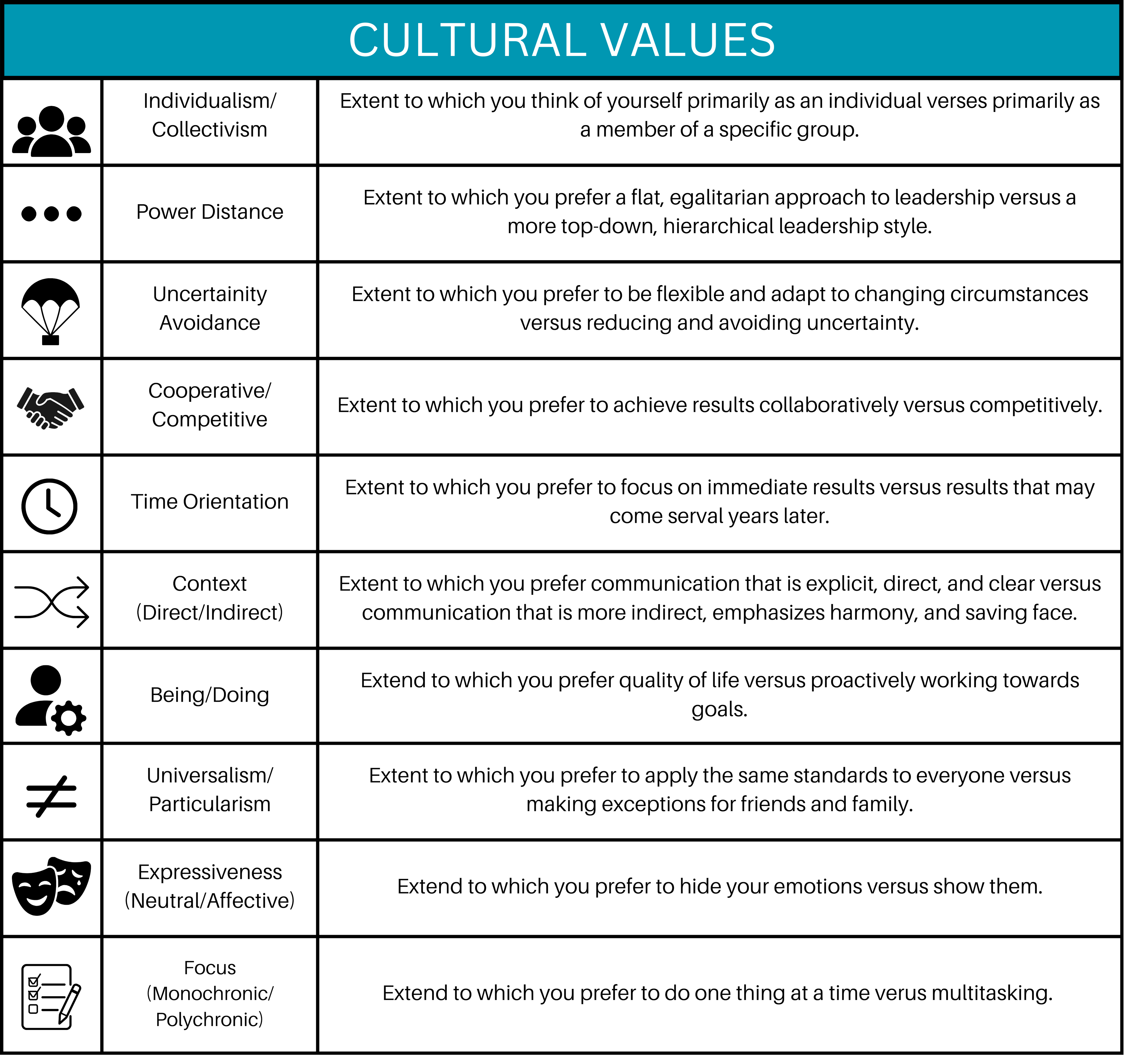

Miscommunication can occur easily when we assume our way is “normal” or “right,” and fail to see the cultural construction of the lens we view life through. For example, some cultures value directness and assertiveness, while others emphasize harmony and indirect feedback. Some rely on strict schedules; others are more flexible with time. These differences can affect everything from project planning meetings to stakeholder engagement processes. Engineers who practice cultural awareness and intelligence can navigate these differences respectfully and productively. Figure 2.14 provides an overview of how different cultural values that can shape how people work together. Note that many of these values are distributed within cultures, and not simply across them; it is important to avoid stereotyping and generalizations while also being sensitive to cultural differences.

2.7.1.1 Cultural Perspectives on Sustainability

Consider that even the concept of sustainability is not universal. In some Indigenous traditions, the land is treated as a living relative rather than a resource. In many Western frameworks, sustainability emphasizes efficiency and innovation. Nordic countries often center collective welfare, while American approaches often highlight individual action. By recognizing these cultural realities, engineers can approach sustainability initiatives with greater empathy, especially when working on cross-cultural or community-based projects. Designing and building infrastructure with relevant sustainability perspectives in mind helps those projects be more socially sustainable by improving buy-in.

Beyond ideas and identity, culture also affects logistics and decision-making. Cultural intelligence in the built environment includes, but isn’t limited to:

- Planning across different time zones and time management norms

- Navigating unfamiliar power dynamics, role expectations, and hierarchies

- Understanding verbal and non-verbal communication preferences

- Recognizing different approaches to risk, deadlines, and authority

Cultural awareness means recognizing how culture shapes values and communication, then using that awareness to ask better questions and adapt respectfully. It encourages curiosity, reflection, and learning.

Cultural stereotyping assumes fixed traits about entire groups. It oversimplifies people by applying generalized beliefs about a cultural group to every individual in that group.

Being culturally aware means using culture as a lens to ask better questions. Stereotyping uses culture as a shortcut to make premature assumptions.

2.7.2 Empathy in the Built Environment

Empathy is understanding a person from their frame of reference rather than one’s own, or vicariously experiencing that person’s feelings, perceptions, and thoughts. In the built environment, practicing empathy helps professionals imagine how different people experience various infrastructure and letting that mold equitable decision-making.

People’s perspectives on infrastructure are shaped by personal and collective history. A family displaced by highway expansion may be skeptical of new development. A person without access to a car may see sidewalks and public transit as essential, not optional. Cultural norms, socioeconomic status, and lived experience all influence how people evaluate what is “needed,” what is “safe,” and what is “fair.” As an engineer or construction manager, developing empathy helps you move beyond your own default perspective to engage with stakeholders more thoughtfully.

Empathy is also an important skill in teamwork. Empathetic leaders understand and share the feelings of their team members, which builds trust and strengthens relationships. This understanding allows leaders to address the concerns and needs of their team more effectively, leading to higher job satisfaction and productivity, improved decision-making and more open problem-solving. Empathetic leadership promotes team cohesion, as team members are more likely to support each other and work collaboratively towards common goals.

Consider the following examples of moments when Christ showed empathy in his mortal ministry: John 11:33-35, John 8:7-11, and 3 Nephi 17:5-6. How can you show empathy in your own life like Jesus did?

Strategies for developing empathy can include the following:

- Serve others By serving the people you’re striving to develop empathy for, you directly engage with their needs and struggles. This fosters increased understanding and love. Elder Gong has promised, “Kindness opens understanding.”

- Practice Active Listening Focus on truly hearing what someone else is saying without planning your response while they’re speaking. This builds trust through being more present, allowing you to grasp others’ perspectives better and helping them feel heard.

- Read Fiction or Engage with Stories Reading books, especially fiction, or listening to personal stories can help you experience the world from another person’s viewpoint. Studies show that exposure to complex characters and varied human experiences can enhance empathy and emotional intelligence.

- Reflect on Your Biases Reflect regularly on personal biases/judgments that may cloud your view of others. Seek out perspectives that challenge your assumptions. This allows you to move past automatic judgments and approach others with more openness.

2.7.3 Unconscious Biases

This last strategy deserves a more in-depth look. A bias is an inclination or prejudice either in favor of or against a particular thing, person, or group. While a few of our individual biases may be conscious, deliberate choices (for example, a bias towards our favorite sports team), most of our biases are unconscious. Biases are mental shortcuts that we form that often assign labels or attributes to a person or group based on limited information about them. This limited information is usually apparent at a surface-level observation and can include factors like race, gender, education level, marital status, age, sexual orientation, political preferences. Most biases represent unfair assumptions about people without getting to know them or empathize with them as an individual. This bias impacts relationships, communication, leadership, and decision-making, often with unintended consequences. Some common biases include:

- Affinity bias: showing favor toward those more similar to us

- Perception bias: making assumptions about people or groups based on stereotypes or group memberships

- Halo effect: projecting positive qualities onto people without actually knowing them

- Confirmation bias: accepting information which reinforces one’s previously held beliefs while disregarding information which challenges it

As we meet and interact with people, it is our responsibility to treat everyone with empathy and without bias.

In JST Matthew 7:1-2, the Lord commands, “Judge not unrighteously, that ye be not judged; but judge righteous judgment.” Ponder on the difference between righteous and unrighteous judgment.

In John 7:24, Jesus gave some clarification: “Judge not according to the appearance, but judge righteous judgment.” Consider this quote from Patricia Holland at a BYU devotional:

The Lord uses us because of our unique personalities and differences rather than in spite of them. He needs all of us, with all our blemishes and weaknesses and limitations. … How does one fill the measure of his or her creation? We do so by … rejoicing in our uniqueness and our difference [and] by remembering that what God really wants us to be is someone’s sister, someone’s brother, and someone’s friend.

Homework and Activities

HW 2.1: Indicators

Develop goals and associated KPI’s related to your team project. These may be indicators related to participation in meetings, the number of meetings you hold, the quality of the meetings, etc. They may also be related to target completion of the project, or other indicators you feel will help keep your team accountable and inform your overall performance.

Document your KPI’s, and track them throughout the term project. Include a description of the indicators and your accounting of them in your term project report.

HW 2.2: Feedback

Develop a process to seek feedback on your term projects at stages when it will be most useful to you. That is, if the only feedback you receive is your grade, you may not have maximized your ability to succeed in this project! This feedback can come from internal KPI’s, from other teams, from TA’s, or from the professor.

Document your feedback and responses to it in your term project report.